It’s National Physicians Week, and as we continue to deal with #COIVD19, we are highlighting and celebrating some of the women pioneers of medicine.

From way-makers to society-shakers, the women of medical history have changed not only the access for women to medical degrees and positions, but also the treatment of those around the world.

Here are 10 women who paved the way for women in medicine and a better livelihood for all.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910)

The first woman in America to receive a medical degree, Elizabeth Blackwell is remembered as the reason many women are in the medical field today.

Elizabeth moved with her family from England to Ohio in 1832 and was inspired to pursue medicine because of something a dying friend once told her: that her situation would have been better if she had a female doctor.

Elizabeth faced many obstacles on her path to medical school and continued to fight for women’s access to such an education after her graduation. She opened her own medical college for women in New York City.

“It’s not easy to be a pioneer- but, oh, it is fascinating! I would not trade one moment, even the worst moment, for all the riches in the world.”

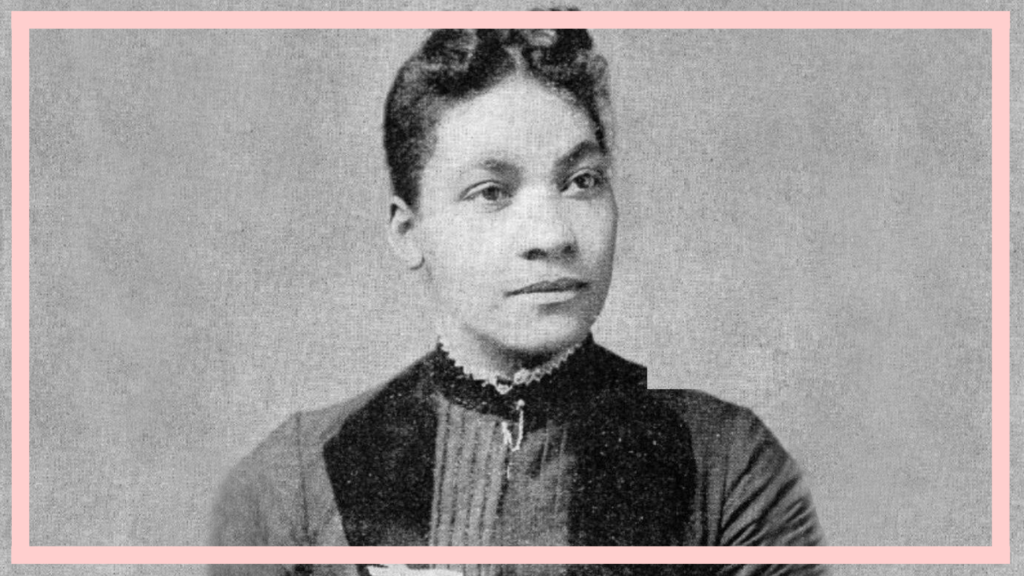

Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831-1895)

Rebecca Lee Crumpler was the first female African American doctor after receiving a medical degree from New England Female Medical College in 1864.

Not much is known about her outside of her book, “Book of Medical Discourses,” which was one of the first medical publications by an African American. Rebecca also cared for freed slaves with other African American physicians who would have had no medical care otherwise.

“I early conceived a liking for, and sought every opportunity to, relieve the sufferings of others.”

Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865-1915)

The first American Indian to receive a doctorate, Susan La Flesche Picotte’s collegiate career wouldn’t have been possible without federal aid for a professional education, which she was the first to receive.

As a kid, Susan watched a local Indian woman die because a white doctor would not care for her. This event inspired Susan to pursue her medical degree so that she could provide care and fight for American Indian living conditions.

Susan provided care to over 1,300 people over 450 square miles, and gave financial advice and resolved family disputes 24/7.

“We who are educated have to be pioneers of Indian civilization. The white people have reached a high standard of civilization, but how many years has it taken them? We are only beginning; so do not try to put us down, but help us climb higher. Give us a chance.”

Mary Edwards Walker (1832-1919)

Over 3,500 people have received the Medal of Honor, and only one was female.

Mary Edwards Walker was the first and only woman to receive the Medal of Honor after her courageous actions as the first female surgeon in the Army. Mary entered the Civil War after struggling to find an opportunity to serve her country. She actually served wounded men as a nurse before risking her life as a frontline surgeon.

In addition to helping pave the way for women to serve as Army surgeons, Mary fought for women’s rights in general, wearing pants to advocate for “dress reform.”

“You must come to terms with the reality that nothing outside ourselves, be it people or things, is actually responsible for our happiness.”

Gerty Cori (1896-1957)

Born in Prague, Gerty Cori received her doctorate in medicine from the Medical School of the German University of Prague. Gerty became a professor of biochemistry and spent many years conducting research with her husband.

In 1947, Gerty and her husband received the Nobel Prize in science for discovering the enzymes that convert glycogen to sugar and back into glycogen again. This made Gerty the first woman in the U.S. to receive a Nobel Prize in science.

“For a research worker, the unforgotten moments of his life are those rare ones which come after years of prodding work, when the veil over nature’s secret seems suddenly to lift and when what was dark and chaotic appears in a clear and beautiful light and pattern.”

Virginia Apgar (1909-1974)

The first full professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Virginia Apgar faced adversity as she sought to receive her medical degree to become a surgeon.

Virginia was told not to continue her education as a female surgeon, but persevered to create the Apgar Score, which stands for “Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity and Respiration.” The score is the first standardized method for reevaluating a newborn’s transition to life outside the womb.

In 1959, Virginia received her masters in public health from Johns Hopkins, and then retired from practice to devote her time to the prevention of birth defects through education and research fundraising. Virginia was pivotal in a change of mission for the March of Dimes in the ‘60s.

“Women are liberated from the time they leave the womb.”

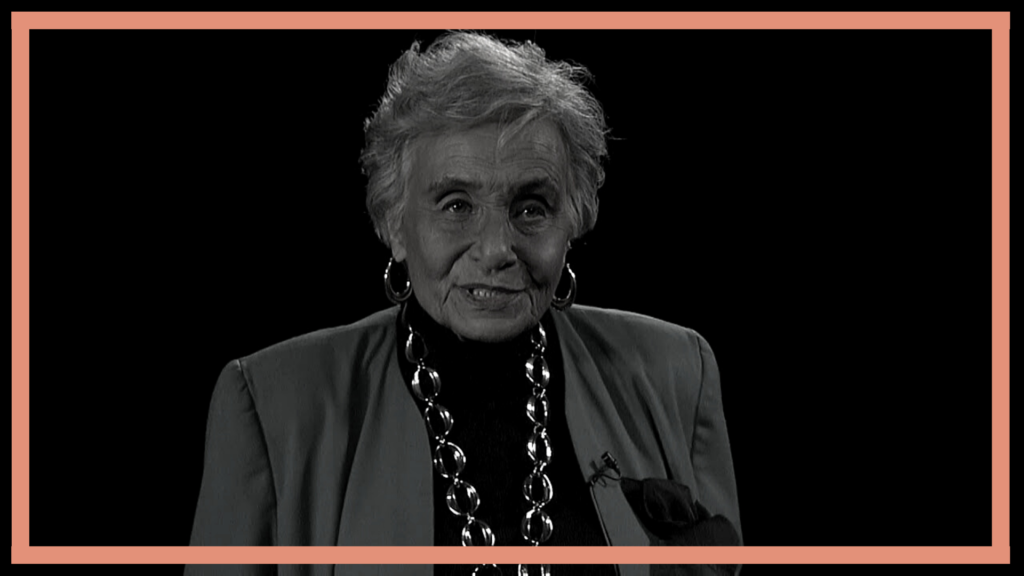

Audrey Evans (1925-)

Audrey Evans knew she wanted to be a doctor since she was five, and moved from England to the United States to find a medical career. Since receiving her degree, she has worked to provide a healthier world for all, especially those with cancer.

Known as a pioneer in the clinical study and treatment of childhood cancer, Audrey developed the Evans Staging System for neuroblastoma. Neuroblastoma is a cancerous tumor that begins in nerve tissue in infants and young children.

Audrey also co-founded the Ronald McDonald camp for kids with cancer in 1987 and helped found the original Ronald McDonald house in Pennsylvania in 1984.

“Good education is the way you get along in the world.”

Joycelyn Elders (1933-)

When Joycelyn Elders heard Dr. Edith Irby Jones speak, she knew she wanted to follow in Dr. Jones’ footsteps and attend the University of Arkansas Medical School to improve the lives of children.

Joycelyn became the first woman, and person in general, in Arkansas to become a board-certified pediatric endocrinologist and the first African American woman and second woman to lead the U.S Public Health Service.

In 1987, Joycelyn was appointed by Governor Bill Clinton to head the Arkansas Department of Health where she campaigned for clinics and expanded sex education. Two years later, Arkansas legislature passed that included sex education, substance abuse prevention and programs to promote self esteem. In 1993, President Clinton appointed her U.S. Surgeon General.

“You can’t educate a child who isn’t healthy, and you can’t keep a child healthy who isn’t educated.”

Marilyn Hughes Gaston (1939-)

When Marilyn Hughes Gaston’s mom fainted due to cervix cancer, she had limited access to healthcare. That day was the day Marilyn decided she would become a doctor, but she was encouraged not to pursue her dream because she was poor and African American.

This didn’t stop Marilyn, who became the first African American woman to direct a Public Health Service Bureau in 1990. Before receiving this position, Marilyn worked with the National Institute for Health as a medical expert and later as a deputy branch chief for the Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) Branch.

In 1986, Marilyn published a groundbreaking report that proved the effectiveness of giving children suffering from SCD long-term penicillin treatment to prevent septic infections.

“What you learn from a mentor is as important as what you learn in a classroom.”

Antonia Novello (1944-)

Antonia Novello was named the first woman and first person of Hispanic-origin to serve as the Surgeon General of the U.S. by President George H.W. Bush in 1990, and her interest in a medical career began at a young age.

Suffering as a child with a medical condition that could only be cured by surgery, Antonia’s family could not afford the surgery until she was 18, and a follow-up surgery at age 20. Through her experience, Antonia decided to be a doctor when she was a teen.

Past her time as U.S. Surgeon General, Antonia was a representative to the United Nations Children’s Fund from 1993 to 1996, a visiting professor at Johns Hopkins from 1996 to 1999 and commissioner of health for the state of New York starting in 1999.

“Service is the rent you pay for living, and that service is what sets you apart.”